Bitcoin Wealth Is Becoming More Evenly Distributed Over Time

Widespread Estimates Of Individual Bitcoin Ownership Concentration Are Oversimplified And Irrelevant.

This content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as investment, financial, or other advice.

Individual Bitcoin holders’ ownership distribution has been a highly debated topic since its inception. Alarming numbers indicating heavy Bitcoin wealth concentration have been circulating around for several years.

In this article, I examine if those widespread estimates are true. Besides that, I highlight other important information when it comes to Bitcoins wealth distribution among its users. I attempt to put these matters into a broader context.

A quick overview of the main chapters:

Bitcoin: Enabling independent and unprecedented real-time forensic analysis

Calculating individual Bitcoin holders wealth distribution: Essential variables

Analysis of commonly cited news regarding Bitcoin wealth concentration

Bitcoins early distribution history

How Bitcoin wealth distribution has changed over time

Global wealth distribution trends

Wealth distribution of other cryptocurrencies

Conclusion

If you find any wrong assumptions and/or conclusions made in this article, please reach out to me so that the article can be continuously improved upon. In this way, the article becomes a more reliable source for other readers over time.

1. Bitcoin: Enabling independent and unprecedented real-time forensic analysis

The transparent and immutable nature of the blockchain allows unprecedented real-time analysis, as was not possible with any other monetary system in history. The sheer amount of unaltered historic data that can now be aggregated, visualized, and interpreted from the Bitcoin blockchain teleports economic analysts into a new world - uncharted territory. This enables posthoc analyses of large-scale market behavior. The capability of reliably interpreting the data - on the other hand - is not seldomly overestimated by researchers and journalists, which will remain immediately relevant for this article when looking into the often cited claims of Bitcoin ownership concentration.

I provide just two examples of real-time datasets available to the interested Bitcoin observer in the next paragraphs (1.1. and 1.2.):

Circulating and maximum supply

Bitcoin monetary inflation

These examples showcase the transparency of the network, but also some of the limitations of interpreting that data.

1.1. Circulating and maximum supply

Anyone interested can independently verify the currently existing Bitcoin supply (~18,95 million)1 and the maximum supply of almost 21 million.2 With gold, in comparison, we can only estimate the below-ground stock reserves (~57,000 metric tons)3 and we trust how much is currently held in various vaults worldwide (which, of course, are independently audited - the difference being: it cannot be audited by anyone at any given time). The US has the largest gold reserves in the world with approximately 8,133 metric tons,4 which may be audited every five years if the “Gold Reserve Transparency Act of 2021” (H.R.3526) goes through some time in the future.5 With fiat currencies, like the US Dollar or the Euro, the circulating supply cannot be audited in real-time independently and transparently, because the architecture of the system does not enable such features, but also because supply exists both in the digital and physical realm. E.g., to learn about the circulating supply of physical Euro banknotes and coins, one can look into the reports of the European Central Bank, which are updated on the 14th day of every month.6 With Bitcoin, on the other hand, the entire ledger is updated roughly every 10 minutes. Although the circulating supply of Bitcoin can be precisely verified at any given point in time, it is important to note that 12 to 20% of those Bitcoins are estimated to be lost (more on this in 2.4.).7 This is one of the numerous examples that showcase a paradox of Bitcoins transparency; Yes, everything is out in the open, but no, we cannot calculate everything with these numbers.

1.2. Bitcoin monetary inflation

The Bitcoin protocol, including the rate of production, is publicly available for everyone to audit at any given time.8 Precisely 6,25 Bitcoins are produced on average every 10 minutes until the next block halving occurs in ~813 days,9 after which the production rate equals 3,125 Bitcoins per 10 minutes. This process of block halvings continues until all ~21 million Bitcoins are mined. The monetary inflation rate is currently at 1,79%10 and it is highly predictable (e.g. ~0,1% in 2034 and ~0,003% in 2058).11

Critical voices will argue that these rules can be changed in the “book of Bitcoin rules”, therefore it is important to understand how rule changes are implemented. In short, no single entity or small group of entities can change the rules. No matter how many Bitcoins you have in your possession, you do not have more “voting” power over other voices - the same goes for miners.

In the end, the community as a whole can never be forced to adopt undesirable changes to Bitcoin. Should a bad actor or group thereof take Bitcoin in a poor direction, the community can rally behind the better version of the project and choose their software. With the community’s economic activity taking place on the better version of the project, the bad actors would find themselves maintaining an empty blockchain while their supporting miners waste computational resources on worthless coins.12

Specifically, the monetary inflation rate and the capped supply of ~21 million units are without a doubt the two “rules” of the protocol that will be the very last to ever be altered - if those two rules were to be changed, two main value propositions of Bitcoin would be immediately diminished, resulting in the devaluation of Bitcoin itself. That would be similar to asking everyone to burn all their money and then 95% of people doing exactly that. On top of that, the original chain with the superior traits (here: fixed supply and predictable rate of production) remains to exist.

2. Calculating individual Bitcoin holders’ wealth distribution: Essential variables

Although various Bitcoin datapoints are publicly recorded and stored on an immutable ledger, interpreting some of that data - as mentioned - is not as easy as it seems at first glance. A prime example of this is to what degree the ownership of individual Bitcoin owners is concentrated. Providing rough estimates of the individual Bitcoin investors’ ownership concentration is a non-trivial task - Pinpointing it is impossible. In the next chapters, I elaborate on why this is an impossible task. For that matter, we will take a closer look at some of the variables that are important to consider when attempting to calculate the ownership concentration. Almost all of the following variables heavily skew the distribution of Bitcoin ownership in a more concentrated fashion when not accounted for in the calculation.

2.1. Exchange wallets

Exchange wallets account for millions of individual users. Today, only four Bitcoin addresses with more than 100,000 Bitcoins exist.13

All four of these “accounts” belong to exchanges, including the third richest address (1P5ZED), which has been thoroughly analyzed by many different sources (most recently in the working paper I examine in chapter 3.3.).14

Two years ago, in January 2020, there were seven Bitcoin addresses with 100,000 BTC or more. All seven belonged to exchanges.15

Not accounting for exchange addresses heavily skews the distribution of Bitcoin ownership in a more concentrated fashion. A significant amount of media publications reporting on Bitcoin ownership concentration have not considered this very basic variable in their estimates which we will see further down the article (Chapter 3.). Pinpointing the exact number of cryptocurrency exchanges is a significant challenge in itself, which is highlighted in 2.10.

2.2. Users can have multiple addresses

A single Bitcoin address does not equal a single Bitcoin user. A single Bitcoin user can easily create hundreds of wallet addresses and distribute their individual holdings across these addresses with ease. It is also common practice to create a new address every time a user, an exchange, or a miner receives a new transaction.

The following graphic - with not-up-to-date numbers from 2018 - visualizes this matter; 25 million private wallets with 460 million addresses in total.16

To account for this, methods of so-called “address clustering” have been introduced in the past, which are becoming more sophisticated over time.

“The goal of address clustering is to group addresses into clusters such that each cluster contains the addresses under the control of one user.”17

There are basically two most widely used methods for Bitcoin address clustering:

“One is based on the multiple input addresses of transactions. The other is based on one-time change addresses.”18

Yet again, significant limitations to identifying address clusters in a reliable fashion are prevalent. The key limitation of clustering methods is that it is difficult to judge the quality of the suggested clustering heuristic due to a lack of large-scale truth labels indicating which addresses genuinely belong to the same user. Additionally:

[…] many addresses could still fail to be clustered into a single entity. After all, not all heuristics and clustering algorithms will always be immediately triggered, especially if coins don't move on-chain.19

The third method for clustering Bitcoin addresses, a “reuse-based heuristic” described in a research paper in 2020, shows that it is a more powerful method for address clustering:20

“[…] the ratio of address reduction contributed by it is approximately 45.12% on average.”

These examples provide us with a sneak preview of how much the results for calculating individual Bitcoin ownership depend on the methodology used - and many more variables are coming up in the next chapters.

2.3. Peeling Chains

Additionally, to obfuscate the tracing of Bitcoins, transactions are often channeled through many different addresses, resulting in so-called peeling chains.21 This is a common practice for criminals, e.g. as was done after the Bitfinex hack of 2016.22

The peeling chains technique is also commonly used by other entities:

It is seen after large transactions from exchanges, marketplaces, mining pools and salary payments. In a peeling chain, a single address begins with a relatively large amount of bitcoins. A smaller amount is then peeled off this larger amount, creating a transaction in which a small amount is transferred to one address, and the remainder is transferred to a one-time change address. This process is repeated - potentially for hundreds or thousands of hops […].23

In the working paper examined in chapter 3.3., the researchers found that 256 million addresses are associated with peeling chains.24

2.4. Public and private companies

In 2021 something which was unimaginable just a few years ago, happened: A tiny wave of companies added Bitcoin to their balance sheets.25

In total, public companies hold an estimated amount of ~256,000 BTC. Private companies currently hold more than 174,000 BTC.26

The wallet addresses of these companies are, of course, confidential - they are not publicly known. Most likely they follow best-practice solutions and store their BTC with cold custodial services companies geared for institutions and large amounts. The Bitcoin holdings of public and private companies currently account for more than 2,2% of Bitcoins circulating supply - a significant amount to exclude when attempting to roughly estimate individual Bitcoin holders’ wealth concentration. These wallets often “behave” like individual investor wallets - buying and holding the digital asset - presenting a significant challenge to identify them.

2.5. Bitcoin Funds, ETFs, and ETPs

Since the “ProShares Bitcoin Strategy ETF” became the first Bitcoin-pegged ETF to debut on U.S. markets, several others have followed. The leader of the pack with more than 643,000 BTC is, without doubt, the “Grayscale Bitcoin Trust” fund.27 Often mislabeled as an ETF, Grayscale is the largest Bitcoin investment vehicle on the planet. The Trust’s BTC are stored in cold storage with the qualified custodian Coinbase, according to their own factsheet.28 A company representative commented that they have filed to convert their fund “into a Bitcoin Spot ETF, the application is under review until July 2022.”29 Bitcoins held by funds, ETFs, and ETPs total ~814,000 BTC, which is almost 4% of the total circulating Bitcoin supply.30

2.6. Countries and governments that hold Bitcoin

The small east-European country of Bulgaria apparently holds a whopping ~1% of the circulating Bitcoin supply.31

This news stem from a press release of May 2017 from the Southeast European Law Enforcement Center, in which the authorities have seemingly seized more than 213,000 BTC from a network of criminals.32 The rumor that Bulgaria holds this vast amount of Bitcoins has since spread throughout the global crypto community. But it is unclear if the government has ever really seized this amount of BTC, held onto them since then, or perhaps sold parts of these positions. An article from the Bitcoinist claims “Bulgaria sold all its BTC”,33 but this statement relies on an article from a local news publication dated 1st of April 2018 (April Fools) - and the article is rather sarcastically written (e.g. suggesting to buy a squadron of new aircraft for the army). From my personal “scratching-the-surface” research, it looks like the Bulgarian authorities never actually confiscated any Bitcoin funds:

The information about the confiscated crypto funds was later denied by the head of the Specialized Prosecutor’s Office, Ivan Geshev, now serving as Bulgaria’s Prosecutor General, who attributed the false claim to SELEC. His statement was also supported by Ivailo Spiridonov, then director of the country’s organized crime combating agency, GDBOP.34

There is reasonable doubt of Bulgaria’s Bitcoin holdings, meaning they could be entirely crossed out of the above table. It is important to note that other countries holding BTC are not listed in the table, e.g. the USA and China. There are several cases where the Chinese and US confiscated a significant amount of Bitcoin from criminals - perhaps the most elegant form of acquiring the digital asset. Last year, Chinese authorities seized almost 195,000 BTC from the PlusToken Ponzi crackdown (more than 1% of the circulating Bitcoin supply).35 In recent news this month, the U.S. Department of Justice announced they have seized $3.6 billion worth of Bitcoin linked to the 2016 hack of the crypto exchange Bitfinex.36 The DOJ says this is the largest financial seizure by U.S. law enforcement. The ~94,640 BTC are held on the address bc1qazcm763858nkj2dj986etajv6wquslv8uxwczt, which is currently the fifth richest single Bitcoin address in existence.37 The US Marshals Service is in charge of auctioning off the government’s Bitcoin holdings - it has seized and auctioned over 185,000 BTC since 2014 (potential USD gains missed: ~6,4 billion USD)38 - an example of such an auction can be seen here.39

It is also worth mentioning that early Bitcoin adopter and software developer Gavin Andresen visited the CIA headquarters as early as June 2011 to give a presentation about Bitcoin40 - there is no conspiracy to be constructed out of this simple presentation - but it cannot be ruled out that government agencies like these have since accumulated a substantial amount of Bitcoin holdings. The summer of 2011 was indeed an interesting time in Bitcoins price history: a “flash crash” from 32 USD to 0,01 USD occurred.41

In summary, it is unclear how many Bitcoins are held by which governments (El Salvador being an exception). The purpose of these subchapters 2.1. to 2.16. is not only to show the number of variables to account for when calculating wealth concentration but also how fogged the variables themselves can be. This becomes quite clear with this particular variable, as numbers vary wildly depending on the source one looks into. To calculate individual investors’ wealth concentration in Bitcoin, these numbers (which are unknown!) would need to be extracted and/or broken down to the individual number of users represented by these holdings. If ignored, the “calculated” estimate will automatically result in a concentrated number far off from reality.

2.7. Lost Bitcoins

Another essential variable to include in the equation is lost Bitcoins. Lost Bitcoins refer to BTC that are not any more accessible to the user - e.g. because the owners lost their private key or passed away without passing on this necessary information beforehand. In Bitcoins’ early days, it was often seen as nerd money or some funny form of an experiment - remember a single Bitcoin was worth nothing for the first years. This resulted in a high level of ignorance when it comes to Bitcoin storage security. A well-known example of this is a young man who accidentally threw away his hard drive with the private keys of 7,500 Bitcoins (today worth more than 260 million USD).42

Several of the richest Bitcoin addresses haven’t seen a single outgoing transaction for over a decade.43 For example, in the Bitcoin rich list currently residing in 30th place, the address 12ib7dApVFvg82TXKycWBNpN8kFyiAN1dr worth more than 1,3 billion USD as of this writing (31,000 BTC), had its last outgoing transaction almost 12 years ago (July 2010). In fact, 10% of all existing Bitcoins have not been moved for over a decade, as the blockchain analytics company Glassnode finds.44 It remains speculative if these BTC are lost or not, but it is not unlikely. John W. Ratcliffe compiled a Spreadsheet of “Dormant Bitcoin Addresses”, which could have been lost. The leading blockchain analytics firm Chainalysis estimates a lower bound of 2,3 million Bitcoins lost and an upper bound of 3,7 million.45

The unknown Bitcoin inventor Satoshi Nakamoto mined between ~1,000,00046 to 1,125,150 Bitcoins.47 It is unclear if Satoshi Nakamoto is still alive and/or has access to the keys. The first Bitcoin transaction, sent by Satoshi, was received by Hal Finney, who passed away in 2014 and is now cryopreserved.48 Hal Finney is often perceived as the most likely person to have been Satoshi Nakamoto, because he was the first person (other than Nakamoto himself) to use the software, file bug reports, and make improvements.49 It is not unlikely that Satoshis’ entire Bitcoin stack is “lost”. I elaborate on this statement in chapter 4.

Other, less significant, examples of lost Bitcoins include so-called “burn addresses” which are verifiable unspendable. An example for this weird phenomenon are the addresses “1BitcoinEaterAddressDontSendf59kuE”50 and “1CounterpartyXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXUWLpVr”,51 to which you can send your BTC if you feel like burning money - more than two-thousand Bitcoins have been sent to these addresses in the past years.52 You can see a list of burn addresses here.

Although the exact total number of lost Bitcoins remains to be highly speculative, it is grossly negligent to simply dismiss this important variable when calculating wealth concentration (12-20% of all BTC).

2.8. Wrapped BTC

Wrapped BTC are a tokenized representation of Bitcoin. This enables them to be used on blockchains to which they are not native (e.g. the Ethereum ecosystem).53

Currently, there are around 263,000 BTC wrapped in the WBTC ERC20 token.54

The custodian stores those BTC on wallets that all have a balance of at least 1,000 BTC. Again, given that these coins belong to many investors, the ownership of BTC disperses further across entities.55

This variable is immediately relevant to the widespread claim that 0,01% of individual Bitcoin investors control 27% of the circulating Bitcoin supply (analyzed in chapter 3.3.) because the working paper on which these numbers rely analyzes the top 2,258 Bitcoin addresses with at least 1,000 BTC. Wrapped BTC are not mentioned in the paper, it is unclear if these were accounted for.

2.9. Hacked exchanges

The infamous Bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox has been hacked several times. One of those hacks occurred in March 2011, in which ~80,000 BTC were stolen.56 Hackers transferred the full amount to a single BTC address:57 1FeexV6bAHb8ybZjqQMjJrcCrHGW9sb6uF.

Until today, over a decade later, this address has no single outgoing transaction, which could signal that the hackers have lost the private key to access the digital assets currently worth more than 2.8 billion USD. This address is currently the 9th richest Bitcoin address.58 Authorities working hand in hand with forensic blockchain analytics companies are becoming more sophisticated in tracking, identifying, and seizing the digital asset BTC from criminals - as the report “Statement of Facts” published by the Department of Justice this month evidently shows.59 The BTC in the “1Feex” address are either “lost” or the hackers will be caught when attempting to launder them (e.g. via peeling chains described in 2.3.). The chance that these criminals will successfully launder the BTC sometime in the future without being caught is minuscule. When attempting to calculate individual Bitcoin ownership concentration, this “1Feex” address might currently be factored in as a single user holding these assets - but given the information outlined in this paragraph, I believe this to be an oversimplified approach. Rather, these BTC can be added in the “lost” column or they will be seized in the future and perhaps even returned to the thousands of users to which they initially belonged.

2.10. Other variables

The variables summarized in this subchapter are not necessarily less important than the ones mentioned above, but this article should not take a full hour to read. Other variables to account for when calculating individual Bitcoin ownership concentration include, but are not limited to:

Mining pools and institutional miners

The chances of an individual miner finding a new block are minuscule. Therefore, individual miners are oftentimes part of a “mining pool”, in which thousands of miners come together to combine their hash rate and increase the probability of ‘finding a new block’. They are essentially trying to be the first to solve a ‘hash puzzle’ by finding the right nonce to validate a new block. First to find the nonce (which occurs roughly every 10 minutes) is rewarded with the block subsidy of 6.25 BTC and all transaction fees on that particular block. Whenever a member of a mining pool solves the hash puzzle, the block reward is distributed among its participants. Tracking the distribution of mining rewards from the pools to the miners is a non-trivial task and the methodology used to achieve this is not seldomly based on unverified (and/or outdated) algorithms.

Dust wallets

Bitcoin dust refers to tiny wallet holdings that are economically unspendable. It costs more (in transaction fees) to spend than the value associated with the Bitcoin address. Users end up with dust in their wallets due to poor transaction management or by receiving dust deposits that were not requested (e.g. via “dust attacks”).60 Assuming that dust wallets represent single users and/or not clustering dust wallets enough, results in a total ‘Bitcoin user number’ far too high off from reality, which in return results in a more concentrated number of individual Bitcoin holders’ wealth distribution.

OTC brokers

There are specific Bitcoin OTC (Over the Counter) brokers that deal with clients looking to place large orders (often starting at 50k USD). Normal methods for obtaining Bitcoin aren't necessarily ideal for high volume transactions, due to trading fees and a limited supply on Bitcoin exchanges. Some investors choose not to have a significant impact on Bitcoin's price and therefore avoid placing massive 'Buy' orders on exchanges.61 Identifying the wallet addresses of OTC brokers presents a significant challenge. It is likely that several addresses belonging to OTC brokers are among the richest Bitcoin addresses - resulting in a significantly more even distribution across single users when accounted for correctly.

Unknown exchange cold wallets

It is difficult to determine the exact number of Bitcoin exchanges since these are not regulated in some countries and therefore do not need to register with any centralized authority. The estimated number of exchanges varies wildly depending on the source you inspect. I’ve stumbled upon numbers ranging from 313 up to 866. On top of not knowing how many exchanges exist, it is incredibly hard to identify the cold wallets of known exchanges:

Because cold wallets typically consist of few addresses and send and receive funds only infrequently, the default clustering algorithm in many cases does not link them to the corresponding hot wallets of exchanges. Therefore, identifying cold wallets presents a significant challenge.62

Of course, several of these exchanges only have a low trading volume and perhaps relatively small wallets, but these small numbers quickly add up to be relevant when calculating individual BTC ownership concentration.

Financial services corporations and asset managers

Fidelity, an American multinational financial services corporation and one of the largest asset managers in the world ($4.9 trillion in assets under management as of 2020)63 started mining Bitcoins in 2015.64 BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager (~10 trillion USD in assets under management as of January 2022),65 invested almost 400 million USD into the two US-based mining institutions Marathon Digital Holdings and Riot Blockchains last year (joining Vanguard Group and Fidelity).66 These indirect investments into Bitcoin via Bitcoin mining stocks enables the mining institutions to expand their mining operations (increasing the hash rate), resulting in more Bitcoins being mined by them. For example, Marathon Digital Holdings currently holds ~8,600 BTC.67 BlackRock has further exposure to Bitcoin via its 7.3% stake in Microstrategy.68 Although the beforementioned asset managers might not be holding Bitcoins directly yet, others, like the Soros Fund Management, own “some coins”.69 It remains unclear how many asset managers control how many BTC.

Even more variables

Many other custodial wallet services (third-parties that hold Bitcoin on behalf of their owners) and more variables to account for when calculating individual Bitcoin ownership concentration exist.70 Some of these include, but are not limited to:

Payment processors (e.g. BitPay)

Bitcoin gambling sites (e.g. SatoshiDice)

Charity funds (e.g. The Giving Block)

Crowdsourced wallets (e.g. Tallycoin)

Family offices

3. Analysis of commonly cited news regarding Bitcoin wealth concentration

Unfortunately, some journalists have published drastically simplified conclusions in the past.

Those statements have since spread like wildfire. Fortunately, repeating wrong numbers on a regular basis does not make them magically come true. In this chapter, we will look into three of those numbers circulating throughout the web when it comes to Bitcoin ownership concentration.

3.1. Claim 1: “2% of Bitcoin holders control 95% of the current supply”

Interpreting Bitcoin data in an oversimplified manner results in wrong conclusions, which results in false narratives. Which in return influences and shapes the opinions of unsuspected readers. An example of this is the highly misleading claim that 2% of Bitcoin holders control 95% of the current supply. This claim has been published in some of the most well-known media outlets of the world:

The Economist - 7th December 2021:

About 2% of bitcoin accounts hold 95% of the available coins, according to Flipside, a crypto-analytics firm.71

Bloomberg - 18th November 2020:

A few large holders commonly referred to as whales continue to own most Bitcoin. About 2% of the anonymous ownership accounts that can be tracked on the cryptocurrency’s blockchain control 95% of the digital asset, according to researcher Flipside Crypto.72

To approach individual Bitcoin ownership in a somewhat professional manner, several variables have to be accounted for as outlined in the previous chapter. In this case, not a single variable was included. Instead, the figures are based entirely on a graph73 visualizing the holdings of the top 2% of addresses in the Bitcoin rich list (image below).74

The Bitcoin rich list simply shows the holdings of Bitcoin addresses - the statement that 2% of addresses control 95% of the supply is true (circled red), but misleading and irrelevant. For comparison, it wouldn’t be fair to conclude that over 97% of the global money stock is owned by a few entities, simply because physical cash accounts for less than 3% of the money in the economy (and only this form of money can currently be held by individuals in the first place without third parties such as banks).75

Raphael Schultze-Kraft, CTO and Co-Founder of Glassnode - a company specialized in data analytics and visualizations of the blockchain - refutes this misleading claim in a well-documented article on the company’s blog.76 The upper bound of individual ownership is that 2% of BTC users hold 71,5% of the circulating supply (instead of 95%).

The […] figures are an estimate for an upper bound of the true distribution of Bitcoin ownership. We expect the actual distribution to be more evenly distributed across entity sizes.

For example, he does not factor in custodians, lost coins, and wrapped BTC. Pushing towards a lower bound might even get you below 50%, which is better than the current global wealth distribution - highlighted in chapter 6 of this article.

3.2. Claim 2: “1,000 people own 40% of all Bitcoins”

Business Insider - 27th of February 2021:

There are around 1,000 individuals, known as whales, who own 40% of the market.77

These numbers were wrong a year ago and still are today. Unfortunately, the author does not reveal the methodology in how she came up with these results. In her article, she also refers to a piece published a month earlier in The Telegraph:

The Telegraph - 22nd of January 2021:

The top 40pc of all Bitcoin, roughly $240bn, is held by just under 2,500 known accounts out of roughly 100m overall.78

The author of this second article links his figures to “industry data”, but it remains unclear which “industry data” these figures rely on. Ignoring the fact that the numbers of both articles vary wildly from one another, the authors do not take into account a single one of the variables mentioned in chapter 2 of this article.

The only explanation I found for the “top 40pc of all Bitcoin […] is held by just under 2,500 known accounts” claim is again the Bitcoin rich list. The numbers on the left and right of the image framed in red are close to the claim cited above. The claim that 1,000 people own 40% of the Bitcoin market, on the other hand, is so remarkably false that I cannot explain it even when ignoring all variables outlined in chapter 2. Perhaps the author based her findings on old figures from several years ago, because - as we will examine in chapters 4 and 5 - individual Bitcoin holders’ wealth was far more concentrated in the past.

3.3. Claim 3: “0,01% of Bitcoin holders control 27% of the current supply”

In a recently published article in the Wall Street Journal, the author claims that 27% of the current Bitcoin supply is held by the top 0,01% of holders.79

In the article, he refers to the non-peer-reviewed working paper published via the National Bureau of Economic Research (October 2021), which was not linked. The paper does not mention these numbers anywhere, as you can verify by reading through the 55 pages yourself.80 Additionally, the working paper is “circulated for discussion and comment purposes”, as stated directly on the cover page. It becomes clear that the paper has not been peer-reviewed when stumbling upon spelling mistakes to an extent that Satoshi Nakamoto is declared to be the “Bitcoin investor” instead of the “Bitcoin inventor”.81

Reading through the paper, the authors have not only presented a method of address-clustering, but they also accounted for many exchange wallets (393 in total) and several other important variables (e.g. 86 gambling sites, 39 online wallets, 33 payment processors, and 63 mining pools) which can skew the distribution metrics significantly. Of the total 2,258 rich addresses that hold a minimum of 1,000 Bitcoins each, they identify that less than 50% of them belong to individuals.82

All in all, I would suggest that this working paper is a good attempt at achieving the impossible: Analyzing the Bitcoin ownership concentration of the “Bitcoin elite”. Summarized in one sentence, the authors state that 10,000 individual Bitcoin investors hold ~5 million BTC. But some variables listed in chapter 2 are missing in the paper.

One of the largest missing variables in their calculations are “lost” Bitcoins - or Bitcoins that cannot be moved anymore (described in 2.7.). The authors refer to them as “forgotten” Bitcoins but don’t subtract them in their final conclusion. Additionally, they may have clustered some addresses too aggressively: Ascertaining that an address belongs to an individual investor because it “acts” like one, is speculative. One cannot assume that every not-yet-identified custodial wallet address automatically translates to be interpreted as the account of a single investor. Additionally, I cannot tell if they accounted for wrapped BTC (described in 2.8.), of which all 265,000 BTC are held in those 2,258 rich addresses they are analyzing. These and other variables - admittedly - are very hard to factor in without adding speculative measures to some degree. But that’s essential: No precise number can be given - instead, numbers should be presented with an upper and lower bound.

The author of the WSJ article takes those findings and further calculates some numbers himself, which he explains in his short article, by doing the following:

10,000 entities hold ~5 million Bitcoins (as stated in the paper on pages 6 and 29)

~114 million individual Bitcoin users as of the time the working paper was published (report by crypto.com - page 8)83

10,000 divided by 114 million = ~0,01%

5 million divided by 18,9 million (circulating supply at the time) = ~27%

Given the beforementioned complexity of estimating individual Bitcoin holders’ concentration, I will not go over my head just to present the reader with “my specific numbers”. It must be acknowledged, that we cannot pinpoint the exact distribution.

Estimates vary wildly depending on the methodology used

The numbers (0,01% control 27%) can be reduced quite easily - and that goes without changing the flawed methodology outlined in the last paragraphs. For example, by simply factoring in the variable “Lost Bitcoins” at its upper bound of 3,7 million,84 the results would disperse significantly. The paper excludes Satoshis coins in its calculations (1 million BTC), so these should already be subtracted from the upper bound of lost Bitcoins as well:

3,7 - 1 = 2,7 million BTC

Especially in the early days, people lost large BTC amounts. It was basically worthless and was easily forgotten on an old hard drive or scrap of paper.85

Assuming that half of the lost Bitcoins belong to the higher entity bucket, we would need to subtract a whopping 1,35 million BTC from the top 10,000 “individual” Bitcoin holdings, resulting in ~19,3% instead of 27%. Global wealth distribution, in comparison, is at ~11% for the top 0,01% (and 6% for the top 0,001%) according to the World Inequality Report of 2022.86 We could also factor in wrapped BTC and many other variables to further skew the distribution numbers dramatically. If someone would want to present a number that “favors Bitcoin”, you could bring that number below 10%. When adjusting the methodology (e.g. not-yet-identified custodial wallet addresses do not automatically mean they are the addresses of single investors), the number of BTC controlled by the 0,01% would be further reduced.

Unfortunately, the claim that precisely 27% of Bitcoins are controlled by 0,01% of individual Bitcoin holders has spread throughout the internet. Note that the working paper was already published two months prior to the WSJ article I refer to above. However, on the same day, the WSJ article was published, the same numbers were cited by other online media outlets such as Fortune.com.87 Within a day, you would find the numbers spread far and wide:

Germany: ”0.01% of bitcoin holders control 27% of all coins: study” (Cointribune)

Austria: “Bitcoin 100 times more unfairly distributed than US dollars” (Der Standard)

Netherlands: ”27% of all bitcoins owned by just 0.01%” (Crypto Insiders)

Nigeria: “0.01% of bitcoin holders control 27% of the currency in circulation” (Nairametrics)

UK: “Top 0.01% of Bitcoin holders control nearly a THIRD of the digital currency worth $232 billion in a dangerous level of concentration, study finds” (Daily Mail)

In the next chapter, we will dive into Bitcoins’ early distribution history - how everything began. Understanding Bitcoins’ genesis and early distribution history, in combination with the chapters that follow, is crucial. It paints a picture that helps us understand that the current distribution of Bitcoin - even if the wild numbers we encountered in the last chapter were proven true - is entirely irrelevant.

4. Bitcoins early distribution history

Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper on the 31st of October 2008, in which Bitcoin is described as a new electronic cash system that's fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party.88 No Bitcoins existed at the time, the total supply was zero. Months before the launch of the Bitcoin experiment, the information was publicly available on the internet.

Satoshi gave everyone a two month heads up before mining the Genesis block, reaching out to the only other people who would possibly be interested in experimenting with a sovereign digital currency at the time, the cypherpunks (via public e-mail list).89

On the 3rd of January 2009, the pseudonymous inventor mined the first Bitcoin block (also known as the Genesis block) for which he was rewarded 50 BTC90 to the address 1A1zP1eP5QGefi2DMPTfTL5SLmv7DivfNa.91

The block subsidy (50 BTC) received by this address cannot be spent - it remains unclear if this was done on purpose or by accident.92 Although he could have continued mining 50 BTC roughly every 10 minutes from then on, it took him a full six days to mine the second block.93

Timestamps for subsequent blocks indicate that Nakamoto did not try to mine all the early blocks solely for himself.94

No pre-mining95 took place, there were no private or public pre-sales96 and every Bitcoin was worthless at the time. The supply started at zero and every Bitcoin in existence - until today - had to be mined via the proof of work algorithm. More than two years went by until one Bitcoin was worth 1 US Dollar.97 Of all cryptocurrencies in existence today, Bitcoin is naturally the only one where early adopters/investors could not realistically expect to make profits: It was the first-mover (no prior history of crypto to base your investment case on) and worthless for over two years.

The early pioneers were the ones crazy enough to take the financial, temporal and social risks to participate in the Bitcoin project, keeping it alive and acting as arbiters of the system in its early days.98

All other cryptocurrencies started at a price above zero (including other pioneer projects like Dogecoin at $0.0005599 in 2013 and Ethereum at $0,31 in 2014).100 Bitcoin’s distribution process was completely open and Satoshi Nakamoto has never cashed out or used his ~1.125 million coins (an exception being the first Bitcoin transaction worth 10 BTC on the 10th of January 2009 to Hal Finney).101

This selflessness has not been replicated by almost any other cryptocurrency, where the founders usually grant themselves large amounts of a coin before the project is even launched, and then sell the token at its peak to realize a large profit.102

The initial miners spent energy mining 2-3 million coins which were worth nothing. Those who risked capital on those initial endeavors should be rewarded. Satoshi then decreased his hash rate over time and hasn’t come back to touch those initial coins:

Once the network grew and more miners joined, it appears that Nakamoto stopped mining in May 2010. “The timing of the shutdown, the mining behavior, the systematic decrease in mining speed and the lack of spending strongly suggest that Satoshi was only interested in growing and protecting the young network”103

The inventor had made Bitcoin the fairest launch that you could conceptualize.

The only real hurdle was knowledge of Bitcoin’s existence, a hurdle which the Bitcoin community has worked hard to eliminate.104

The extreme price volatility since Bitcoin first started trading on exchanges - with its boom and bust cycles - continues to create headlines in newspapers around the world on a regular basis, resulting in a 24/7 free and global marketing campaign for Bitcoin which every PR agency could only dream of achieving for their clients.

Bitcoins’ early distribution history is an interesting and important topic to learn about - this chapter could easily be extended by several paragraphs - but I will leave it as it is for now. If you want to learn more about the early distribution process of Bitcoin, I recommend reading Lyn Alden’s article titled “Bitcoin: Addressing the Ponzi Scheme Characterization”.105 She also dismantles the widespread myth that Bitcoin is a “Ponzi scheme” in her article, a common misconception upheld and perpetuated by people with little to no Bitcoin knowledge.

5. How Bitcoin wealth distribution has changed over time

In chapter 2 we learned about the various number of variables to consider when attempting to estimate individual Bitcoin holders’ wealth concentration. It became clear that several of the listed variables simply cannot be decrypted in a reliable fashion - this automatically results in a (somewhat unsatisfactory) wide range of estimates with an upper and lower bound for the wealth concentration of individual Bitcoin holders. In chapter 3 we examined some of the most common narratives surrounding BTC wealth concentration and learned how to dismantle those arguments (e.g. by checking if all variables listed in Chapter 2 have been accounted for). Chapter 4 revealed Bitcoins’ early distribution history and shows that the launch was conceptualized arguably in the fairest way possible at the time.

In this chapter, we observe how Bitcoin wealth distribution has changed over the last 13 years. Is it becoming more concentrated or evenly distributed? Which econometric measures can we make use of to find out and are they reliable? Let’s dig deeper.

5.1. Gini coefficient

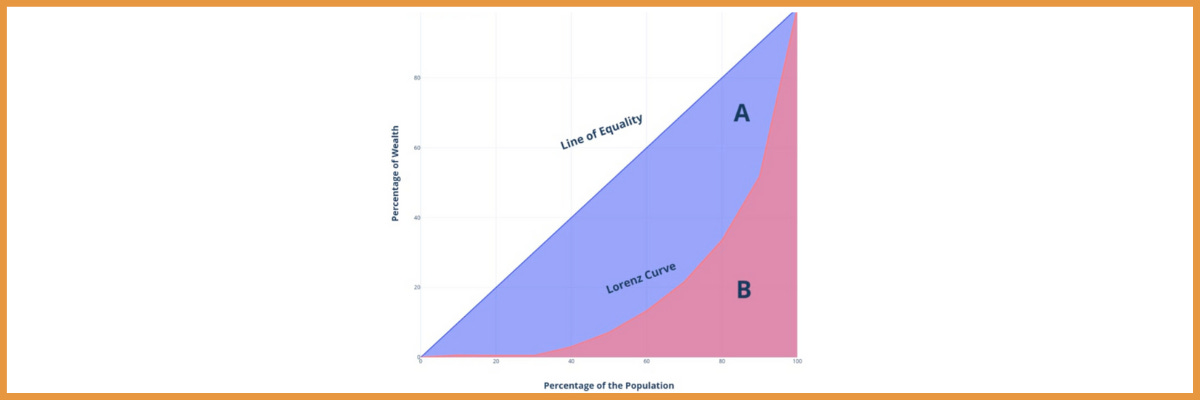

A common statistical construct for describing wealth inequality is the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient compromises the findings of a Lorenz curve into one simple number ranging from 0 to 1. Perfect equality is represented by the number 0, while 1 represents complete inequality.

The Lorenz curve graphically represents the percentage of wealth accumulated by various portions of the population ordered by the size of their wealth.106 The line of equality is at a 45° angle and represents the perfectly equal distribution of wealth (see image above). The area between the line of equality and the Lorenz curve can be used to determine the Gini coefficient: A/(A+B)

Calculating the Gini coefficient for Bitcoin is - once again - not straightforward. Some of the same challenges described in previous chapters present themselves once more: Users can have multiple addresses, custodial wallets represent multiple users, etc. As discussed in chapter 2.3. in regards to peeling chains and dust wallets - hundreds of millions of wallet addresses must be excluded to reliably interpret the blockchain data for these purposes (if not, the Gini coefficient is miscalculated and turns out to be 0.99+). In a recent research article (Dec. 2021) titled “Characterizing Wealth Inequality in Cryptocurrencies,” the researchers start calculating the Gini coefficient of Bitcoin by introducing a requirement of a minimum balance:

For instance, introducing a requirement of a minimum balance of USD 100 for inclusion in Gini calculation can significantly improve accuracy by eliminating several addresses with very low or zero balances.107

To further calculate the Gini coefficient for Bitcoin, they utilized Bitcoins UTXO model of transactions:

To accurately understand the wealth distribution over time […] we need to process all the successful transactions and construct a timeline of balances for all known addresses. The obtained dataset exhibits three characteristics of Big Data: volume, velocity, and variety.

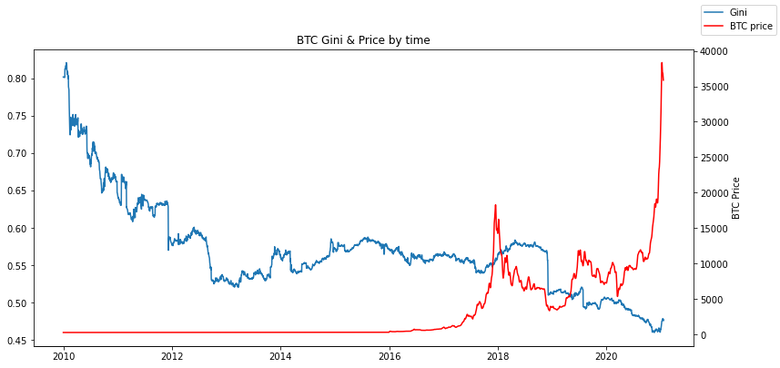

The data is then extracted and analyzed (more info in the paper itself from 3.2. onwards).108 The results for the Bitcoin Gini coefficient over time looks like this:

Since Bitcoin went live on the 3rd of January 2009, the Gini coefficient has been almost steadily declining. The wealth distribution of Bitcoin, according to these recent analyses, is in line with real-world economies. The calculated Gini value for Bitcoin is around 0.65, but according to the graph above (and below), it is around 0.48. When adjusting the wallet clustering method, the Gini coefficient increases up to 0,73.109 Another source from 2019 calculates a Bitcoin Gini of 0.672 (although it only takes the top 10,000 addresses into account).110 Again, it becomes clear that results vary wildly depending on the methodology - but the Gini coefficient of BTC is declining, no matter which recent research one looks into. For comparison:

The average Gini value for the world’s wealth distribution is 0.8; however, it is worth noting that the results vary considerably by country, with a median value of 0.73.111

Cylynx, a company offering blockchain forensics services, came to a very similar result when processing and visualizing their on-chain data of the BTC Gini coefficient:112

The flattening out of the curve is a good sign of general retail interest and holding power of BTC.113

Debunking a widespread Bitcoin Gini falsehood

Similar to the wealth concentration for the top Bitcoin holders, the Gini coefficient of Bitcoin is oftentimes calculated in an oversimplified manner which leads to some bizarre articles. David Rosenthal debunks the widespread myth that the Gini coefficient of “Bitcoin is worse than North Korea” in his blog post from 2018.114 It astonishes me that such easy to debunk misinformation spreads so far and wide in the first place - I quote Mr. Rosenthals blog post:

In his testimony to the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Community Affairs' hearing on “Exploring the Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Ecosystem" entitled Crypto is the Mother of All Scams and (Now Busted) Bubbles While Blockchain Is The Most Over-Hyped Technology Ever, No Better than a Spreadsheet/Database, […] wrote:

wealth in crypto-land is more concentrated than in North Korea where the inequality Gini coefficient is 0.86 (it is 0.41 in the quite unequal US): the Gini coefficient for Bitcoin is an astonishing 0.88.

The link is to Joe Weisenthal's How Bitcoin Is Like North Korea from nearly five years ago, which was based upon a Stack Exchange post, which in turn was based upon a post by the owner of the Bitcoinica exchange from 2011. Which didn't look at all holdings of Bitcoin, let alone the whole of crypto-land, but only at Bitcoinica's customers.115

The Bitcoin Gini of 0.88 is still commonly referred to when debating Bitcoin wealth distribution. I just had someone recently comment using that exact number on my last LinkedIn post. It amazes me that this specific number, which is based on a simple forum post from over a decade ago, still circulates today.116

Caveats of the Gini coefficient

It is important to note that the usefulness of the Gini coefficient in regards to measuring wealth distribution in cryptocurrencies is controversial - opinions differ. For example, Vitalik Buterin, founder of Ethereum, describes the caveats of the Gini coefficient in his article “Against overuse of the Gini coefficient:”117

The Gini coefficient combines together into a single inequality index two problems that actually look quite different: suffering due to lack of resources and concentration of power.118

Acknowledging the weaknesses of the Gini coefficient, especially in regards to non-geographic communities (e.g. internet and crypto), it cannot serve us as the only metric to rely on and conclude that Bitcoin is becoming more evenly distributed. Therefore, we will look into more data to see if it also indicates a better distribution over time.

5.2. Nakamoto index

Another method of measuring wealth inequality is the Nakamoto index. While the Gini looks at the spread of wealth distribution over the whole population of participants, the Nakamoto index is restricted to only the minimum number of participants that control 51% of the wealth in the ecosystem.

Due to this difference, it is possible though unlikely to get a small Gini value (high wealth distribution) with a small Nakamoto index (a small number have 51% control). A small Gini value signifies a fairer wealth distribution among all the participants. A small Nakamoto index represents wealth concentration for only 51% of the wealth distribution in the ecosystem. This result indicates that only a small proportion […] controls 51% of the wealth in the ecosystem; however, over the whole population of all participants, the wealth distribution may be more even. Similarly, it is also possible to get a big Gini value with a big Nakamoto index inferring an uneven wealth distribution over the whole participant population but a more fair distribution in the participants who control 51% of the wealth.119

The Nakamoto index is far more susceptible to rapid changes - it can be readily skewed by a few large transactions from large wallet addresses. The Gini index is substantially more stable and takes into account much more information from numerous addresses. This is how the Nakamoto index for Bitcoin changed over the years:

Bitcoin Nakamoto index stayed low in the early years, with only 1,840 accounts controlling over 51% of all the Bitcoins in the ecosystem until 2012. This value has since increased to 4,652 in 2020, demonstrating a high wealth concentration. However, the trend towards a more even distribution of wealth observed over time in the Gini value can also be seen through the steady increase in the Nakamoto Index’s value for Bitcoin […].120

As learned in chapter 2, these “accounts” include exchange wallets and other variables. Although both metrics have their weaknesses, together they provide us with more expressiveness:

Bitcoin Gini coefficient has declined significantly

Bitcoin Nakamoto index has increased significantly

Both metrics demonstrate that Bitcoin is becoming more evenly distributed over time. The Gini index is better for comparisons and long-term patterns, whereas the Nakamoto index is probably better for capturing events and instantaneous dynamics.121 Next, we take the current global Bitcoin adoption stage into account and take a closer look at how market dynamics (e.g. Bitcoin bubbles) influenced the distribution.

5.3. Early adopters phase and market dynamics

Current estimates signal that the global Bitcoin adoption rate is somewhere between 1-3 percent, depending on the source.122 While that might sound like a small number, Bitcoin is still very young, started at zero, and reached a 1 trillion US Dollar market capitalization in just 12 years. It needs to be acknowledged that Bitcoin is still very much a nascent monetary system, but it has come a long way in a short space of time.

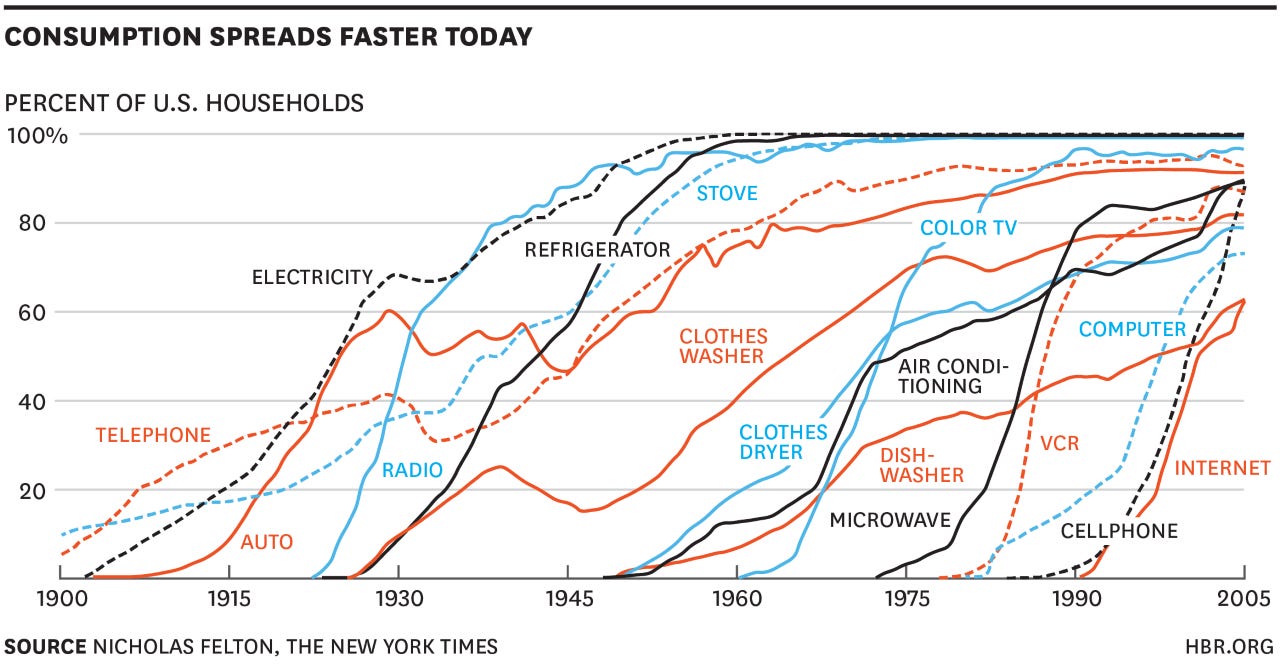

Chainalysis reports that global crypto adoption has surged a whopping 881% last year123 and Bitcoin is being adopted quicker than the internet,124 underlining the theory that the pace of technology adoption is speeding up.125 In regards to user numbers, it took the internet 25 years to get to the point where Bitcoin is now after half the time. Some sources even suggest that the cryptocurrency (including Bitcoin) adoption curve is the fastest in human history.126

While adoption is certainly happening a lot quicker, over 97% of the world’s population is still not onboarded. Reporting on the current Bitcoin wealth distribution while neglecting its short existence, current low adoption, and that its distribution has become much more even over time, can be quite unfair and misleading. Simply put: It is too early to “judge” individual Bitcoin owner distribution at this early adoption stage; instead, the trend is relevant. The market dynamics of Bitcoin, the boom and bust cycles leveraged by its unelastic supply, have also had a positive effect on BTC wealth distribution:

With each of those boom/bust cycles we’ve seen Bitcoin redistributed from old hodlers to new hodlers via selling, decreasing the Gini Coefficient. In 2017 alone, we saw 15% of all BTC move out of old hodler hands.127

“Hodl”, a word based on a spelling mistake in the Bitcointalk forum in 2013,128 simply means “hold” in “crypto terms”. It is not an abbreviation for “Hold on for dear life”, as often propagated. Unchained Capital, an industry-leading company specialized on Bitcoin financial services, introduced “HODL waves” which show that the distribution of BTC increases as the price goes up:129

The colored bands show the reletive fraction of Bitcoin in existence that was last transacted within the time window indicated in the legend. The bottom, warmer colors (reds, oranges) represent Bitcoin transacting very recently while the top, cooler colors (greens, blues) represent Bitcoin that hasn’t transacted in a long time.130

Over the duration of Bitcoin's existence, it becomes clear that the (relative) number of BTC held by smaller entities has increased:131

Note that the above image does not simply show the holdings of Bitcoin addresses over time, but rather the holdings of entities. The visualization is a result of address clustering and advanced data science providing it with more informational significance.132 Additional distribution of Bitcoin among its holders takes place through the decentralized mining process of the last ~10% of total supply over the next ~118 years. Another important factor, often disregarded when discussing Bitcoin wealth distribution, is where the adoption is actually taking place.

5.4. Bitcoin adoption in emerging markets

New technologies are generally adopted quicker in industrialized countries because of various reasons, e.g. they have more resources to invest in research, development, and education. The countries that are good at adopting new technology generally have a higher GDP.133 Additionally, developing countries have to overcome various challenges when adopting frontier technologies, as outlined in the Technology and Innovation Report 2021 published by the United Nations.134 For example, poor infrastructure and financial systems reduce the pace of technological adoption.

Interestingly enough, crypto adoption is growing fastest in emerging markets underserved by existing financial services. The adoption rate is highest in lower-middle income countries:135

A reason for this could be that developing countries tend to have a much higher inflation rate than developed countries,136 so Bitcoin is more often perceived as a hedge and/or provides more value to the inhabitants of such regions. In developed countries, on the other hand, Bitcoin is often interpreted as a speculative tool - the value of an independent, transparent, and scarce monetary asset is harder to detect in a stable and functioning economy. The extreme volatility of Bitcoin is still the highest barrier for investors, as a recent study of Fidelity finds - it tends to keep people away from the new asset.137 Additionally, the demographic pyramid is significantly different in developing countries, which can be visualized to a certain extent by comparing the population pyramids of Africa and Europe:138

Bitcoin is adopted quicker by younger age groups, as recent Pew Research Center finds.139 Furthermore, the vast majority of the ~1,7 billion unbanked people in the world tend to live in developing countries.140 The financial inclusion Bitcoin can theoretically offer to these affected people creates another attractive incentive to make use of it. In El Salvador, for example, 46% of the population has a Bitcoin wallet, whereas 29% have a bank account.141 Bitcoin achieved in a few months what banks could not provide in decades. The combination of smartphone ownership surging in developing countries142 and the internet becoming more accessible worldwide143 provides Bitcoin with even more fertile ground to grow. Peer-to-peer markets are well-established in some sub-Saharan countries like Nigeria and mobile payment methods are commonly used. A recent study underlines the above statements: Bitcoin can contribute positively to reducing the global imbalance of income and wealth distribution because it provides for greater financial inclusion contributing to lower-income/wealth inequality.144

Bitcoin has the potential to help transfer wealth to younger generations because they benefit at the expense of older investors who are positioned later in the curve of technological adoption. It is an alternative to the existing financial system with fewer entry barriers and it levels the playing field for a larger number of participants - a stateless and self-governing digital currency.

Additionally, Bitcoin potentially pushes back on the Cantillon Effect, which refers to the effect that an increase in the money supply is not automatically distributed evenly across all sectors of an economy, with some sectors (in particular the financial sector) benefiting first, while the rest of the economy follows later or does not benefit at all from money creation.145 A case study titled “The impact of monetary systems on income inequity and wealth distribution: A case study of cryptocurrencies, fiat money and gold standard” finds:

[…] that cryptocurrency and gold standard monetary systems contributed significantly to reducing global inequality of income and wealth distribution. Conversely, the traditional fiat money system contributes positively to global income and wealth inequality while also contributing significantly to their fluctuation.146

These findings indicate that global wealth distribution is heading in the opposite direction of Bitcoin; becoming more heavily concentrated - the topic of the next chapter.

6. Global wealth distribution trends

Bitcoin is not a local or country-bound system - it’s global, ignoring the borders of nations. Therefore, to place Bitcoins distribution into a real-world context, it is worth looking into new reports investigating global wealth inequality. As mentioned in chapter 5.3., distribution metrics between the two are not comparable at this early point of time, because Bitcoin is at a 1-3% adoption rate (and still in the early distribution process). But I believe that global wealth distribution and its trends are mention-worthy for this article and show if it has been becoming more concentrated in the past, which would be the opposite of Bitcoin. Just like Bitcoin, it is not an easy undertaking to measure global wealth distribution, as financial globalization makes it increasingly hard to measure wealth at the top:

New data sources (leaks from financial institutions, tax amnesties, and macroeconomic statistics of tax havens) can be leveraged to better capture the wealth of the rich.147

The current distribution of global wealth

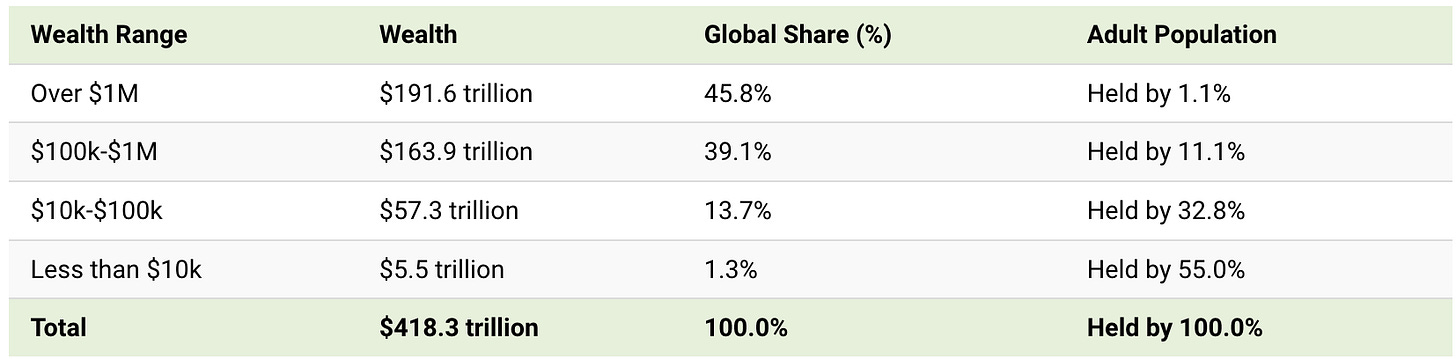

According to the Global Wealth Report 2021 published by Credit Suisse, approximately 45,8% of global wealth is held by the richest 1,1% of the adult population. On the other side of the scale, 55% of the adult population (~2.9 billion) owns only 1,3% of global wealth:148

A graphic based on the findings of the recent Credit Suisse report visualizes the unequal distribution outlined above, the top ~12% own ~85% of global wealth:149

The most recent report published by Oxfam International indicates that the 10 richest people in the world own more than the bottom 3.1 billion people combined.150

Trends of global wealth distribution

Global wealth distribution trends differ vastly from country to country. For example, wealth has become slightly more evenly distributed in Germany over the last two decades, when looking into the Gini coefficient. On the other hand, wealth is becoming increasingly more heavily concentrated in countries like China, where the top 1% now share more than 30% of the wealth, compared to ~21% in 2000.151

Zooming out and observing wealth inequality on a global scale, the trend has been the same for several decades:

Evidence points toward a rise in global wealth concentration: For China, Europe, and the United States combined, the top 1% wealth share has increased from 28% in 1980 to 33% today, while the bottom 75% share hovered around 10%.152

In Russia and the United States, the rise in wealth inequality has been more evident, whereas in Europe it has been more moderate.153 The wide gap in wealth levels between countries is paralleled by the wide disparity in wealth within countries. As for high net worth individuals; they have been increasing their share of global wealth over the last two decades:

HNW are increasingly dominant in terms of total wealth ownership and their share of global wealth. The aggregate wealth of HNW adults has grown nearly four-fold from USD 41.5 trillion in 2000 to USD 191.6 trillion in 2020, and their share of global wealth has risen from 35% to 46% over the same period.154

For example, the world’s ten richest people doubled their fortunes during the pandemic.155 The wealth gap is widening on a global scale.

7. Wealth distribution of other cryptocurrencies

In a recently published research article, the authors measured and characterized wealth inequality in different cryptocurrencies.156 The results indicate that most of the time, the higher the market capitalization of a cryptocurrency the more even the distribution becomes:

“Our findings suggest that major crypto economies are similar to conventional economies in terms of wealth distribution […] however, there is a trend towards more even wealth distribution among large cryptocurrencies over time.”157

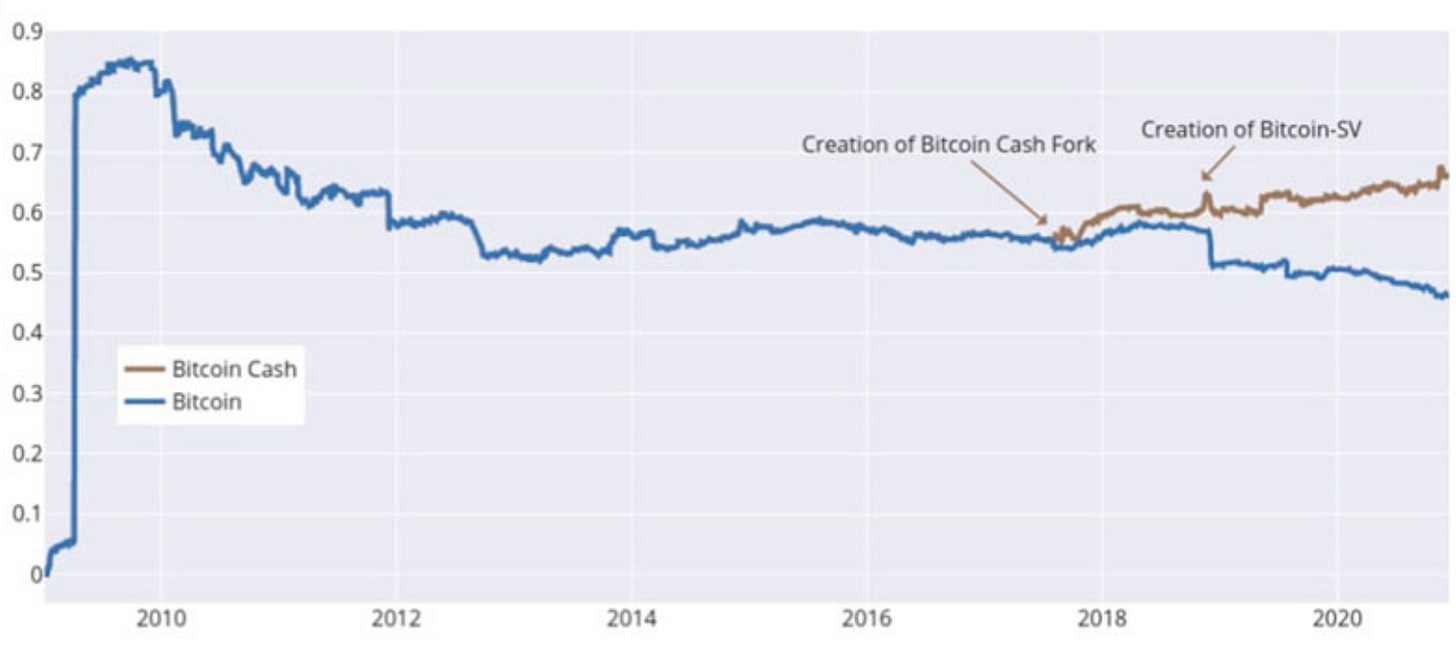

Just like with BTC, the trend of a high Gini value when the adoption is low is prevalent in all other cryptocurrencies analyzed in the research article:158

Overall, there seem to be three distinctive trends in terms of wealth concentration in Bitcoin-like cryptocurrencies: those that tend to on average stay at a higher Gini value than Bitcoin over time (Dogecoin and Bitcoin Cash), those that have a higher Gini value than Bitcoin but demonstrate a slightly downwards trend over time (Litecoin and ZCash) and finally those that have a lower Gini value than Bitcoin but have started to see an increase in their Gini value now (Dash).

The Gini coefficient does not necessarily become lower for all cryptocurrencies over time:

Cryptocurrencies such as Dogecoin do not demonstrate a similar trend towards a fairer wealth distribution despite the increase in adoption. […] unlike Bitcoin, Dogecoin trends towards an increase in the overall wealth concentration.

Dogecoin had the highest observed Gini value of all analyzed cryptocurrencies (0.82), but it is not the only one trending towards an increase of wealth concentration among its users. The same goes for Bitcoin Cash and other Bitcoin forks; they are on a continuous path of increasing wealth concentration since their creation:159

Yet again, the same can be observed with the Ethereum fork “Ethereum Classic”:160

Additionally, some of the observed cryptocurrencies (Dogecoin, ZCash, and Ethereum Classic) violate the honest majority assumption (a very low Nakamoto index) with less than 100 participants controlling over 51% wealth in the ecosystem, potentially indicating a security threat.

Alarming numbers for token projects

The overwhelming majority of all tokens are positioned in the range of a Gini coefficient from 0.9 to 1.0 and a Nakomoto index below 100. In other words, they are very unevenly distributed. For the few token exceptions with a lower Gini coefficient, a token airdrop campaign could have easily changed the distribution, creating an artificially low Gini level. In general, tokens are having a very unnatural and artificial distribution, with high Gini, high Theil, and low Nakamoto index metrics.161

8. Conclusion

Although the public nature of the Bitcoin blockchain enables big data analyses (chapter 1), estimating individual Bitcoin investors’ wealth concentration is a non-trivial task. There are many variables to account for and most of them cannot be accurately determined (chapter 2). The top 2% of the richest Bitcoin owners are estimated to control an upper bound of ~71.5%, while a lower bound could be well under 50% (chapter 3.1.). For comparison, the richest ~1% own ~45% of today’s global wealth (chapter 6). Often cited and widespread news of heavily concentrated individual Bitcoin holders’ ownership are oversimplified and not put into context (chapters 3, 4, and 5). The launch of Bitcoin was conceptualized as fair as possible (chapter 4) and it is too early to present a concluding statement on individual Bitcoin owner distribution at this early adoption stage; instead, the trend is relevant. Despite its young age, BTC distribution is already in line with real-world economies (chapter 5.1.). Bitcoins boom and bust market dynamics, decentralized production, rising price tag, and increasing adoption have significantly contributed to a more even distribution in the past (chapter 5). Individuals in low-middle income countries tend to be adopting Bitcoin faster than people in industrialized nations, possibly leveraging a further wealth re-distribution both from “rich to poor and old to young” (chapter 5.3.). Bitcoin pushes back on the Cantillon Effect (chapter 5.4.) and could positively contribute to reducing the global imbalance of wealth distribution because it provides for greater financial inclusion (chapter 5.4.). Traditional fiat-based monetary systems tend to become more concentrated over time. The rich become richer - the wealth gap has been widening for several decades (chapter 6) while ~1,7 billion people still remain unbanked today. Most other cryptocurrencies are more heavily concentrated than Bitcoin and some are even becoming more concentrated over time (chapter 7).

BitBeginner.com is launching on the 21st of March 2022.

It’s an ad-free, beginner-friendly, education platform focused on Bitcoin. Stay tuned.

Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Sources used in this article:

coinmarketcap.com/currencies/bitcoin or bashco.github.io/Bitcoin_Monetary_Inflation

baloian.medium.com/why-21-million-is-the-maximum-number-of-bitcoins-can-be-created-ecc1ff6edc3d

usgs.gov/faqs/how-much-gold-has-been-found-world?qt-news_science_products=0

tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gold-reserves

congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3526?r=1&s=1

ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/banknotes+coins/circulation/html/index.en.html

blog.chainalysis.com/reports/money-supply

en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Protocol_documentation

bitcoinblockhalf.com

charts.woobull.com/bitcoin-inflation

bashco.github.io/Bitcoin_Monetary_Inflation

galea.medium.com/bitcoin-development-who-can-change-the-core-protocol-478b8ac5fe43

bitinfocharts.com/en/top-100-richest-bitcoin-addresses-1.html

Makarov, Igor and Schoar, Antoinette, Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market (October 13, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3942181 - page 28 - ©

insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin_holders

blog.chainalysis.com/reports/bitcoin-addresses

researchgate.net/publication/347083664_Heuristic-Based_Address_Clustering_in_Bitcoin

researchgate.net/publication/347083664_Heuristic-Based_Address_Clustering_in_Bitcoin

insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin-supply-distribution

ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=9265226

fraudinvestigation.net/cryptocurrency/tracing/peel-chain

elliptic.co/blog/elliptic-analysis-new-york-husband-and-wife-arrested-for-laundering-5-billion-in-bitcoin-stolen-from-bitfinex-in-2016

cseweb.ucsd.edu/~smeiklejohn/files/imc13.pdf

Makarov, Igor and Schoar, Antoinette, Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market (October 13, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3942181 - page 9 - ©

bitcointreasuries.com

bitcointreasuries.com

coinglass.com/Grayscale

grayscale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/GBTC-Trust-Fact-Sheet-February-2022.pdf

marketwatch.com/story/grayscale-investment-wants-its-largest-bitcoin-trust-to-be-an-etf-a-miscue-briefly-made-its-wish-come-11638983263

bitcointreasuries.com

bitcointreasuries.com

selec.org/more-than-200000-bitcoins-in-value-of-500-million-usd-found-by-the-bulgarian-authorities

bitcoinist.com/bulgaria-not-bitcoin-1-6b-finance-minister

news.bitcoin.com/ministries-queried-about-missing-200000-bitcoins-as-bulgaria-explores-crypto-payments

asiafinancial.com/china-confiscates-4-2-billion-in-crypto-assets-from-plustoken-sc

justice.gov/opa/pr/two-arrested-alleged-conspiracy-launder-45-billion-stolen-cryptocurrency

bitinfocharts.com/top-100-richest-bitcoin-addresses.html

jlopp.github.io/us-marshals-bitcoin-auctions

usmarshals.gov/assets/2020/febbitcoinauction

bitcointalk.org/?topic=6652.0

blog.bitmex.com/the-june-2011-bitcoin-flash-crash/

theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jan/14/man-newport-council-50m-helps-find-bitcoins-landfill-james-howells

bitinfocharts.com/en/top-100-richest-bitcoin-addresses-1.html

studio.glassnode.com/metrics?a=BTC&m=supply.ActiveMore10Y&zoom=all

blog.chainalysis.com/reports/money-supply

bitslog.com/2013/04/17/the-well-deserved-fortune-of-satoshi-nakamoto

whale-alert.medium.com/the-satoshi-fortune-e49cf73f9a9b

wired.com/2014/08/hal-finney

bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=155054.0

blockchain.com/btc/address/1BitcoinEaterAddressDontSendf59kuE

blockchain.com/btc/address/1CounterpartyXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXUWLpVr

blockchain.com/btc/address/1CounterpartyXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXUWLpVr

gemini.com/cryptopedia/wrapped-bitcoin-vs-bitcoin-wbtc-tbtc-wnxm-hbtc-crypto#section-wrapped-bitcoin-w-btc-vs-bitcoin-btc

wbtc.network/dashboard/order-book

insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin-supply-distribution

blog.wizsec.jp/2020/06/mtgox-march-2011-theft.html

blog.wizsec.jp/2020/06/mtgox-march-2011-theft.html

bitinfocharts.com/top-100-richest-bitcoin-addresses.html

justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1470211/download

blog.keys.casa/bitcoin-dust-attack-myths-misconceptions

99bitcoins.com/buy-bitcoin/large-amounts-otc-broker

Makarov, Igor and Schoar, Antoinette, Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market (October 13, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3942181 - page 27

fidelity.com/bin-public/060_www_fidelity_com/documents/about-fidelity/corporate-statistics-infographic.pdf

fidelitydigitalassets.com/about-us

ft.com/content/7603e676-779b-4c13-8f46-a964594e3c2f

forbes.com/sites/anthonytellez/2021/08/19/blackrock-joins-fidelity-and-vanguard-as-a-bitcoin-mining-investor

ir.marathondh.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1275/marathon-digital-holdings-announces-bitcoin-production-and

fintel.io/so/us/mstr/blackrock

forbes.com/sites/billybambrough/2021/10/08/george-soros-fund-reveals-surprise-bitcoin-bet-amid-huge-500-billion-crypto-price-surge/?sh=5ea4849c79d1

walletexplorer.com

economist.com/the-economist-explains/2021/12/06/why-have-prices-of-cryptocurrencies-such-as-bitcoin-fallen-again

bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-18/bitcoin-whales-ownership-concentration-is-rising-during-rally

assets.bwbx.io/images/users/iqjWHBFdfxIU/i0GCaEaYgpM8/v0/1200x631.png

bitinfocharts.com/en/top-100-richest-bitcoin-addresses.html

hbr.org/2021/10/what-if-central-banks-issued-digital-currency

hbr.org/2021/10/what-if-central-banks-issued-digital-currency

businessinsider.com/bitcoin-whales-the-key-facts-figures-you-need-to-know-2021-1

telegraph.co.uk/technology/2021/01/22/weird-world-bitcoin-whales-2500-people-control-40pc-market

wsj.com/articles/bitcoins-one-percent-controls-lions-share-of-the-cryptocurrencys-wealth-11639996204

Makarov, Igor and Schoar, Antoinette, Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market (October 13, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3942181 ©

nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29396/w29396.pdf - page 29

Makarov, Igor and Schoar, Antoinette, Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market (October 13, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3942181 - page 28 - ©

assets.ctfassets.net/hfgyig42jimx/29W6quEoTbgrDkrpMPDiFY/6cedbb57db84ec74f02bb8354f69f176/202107_Data_Report_OnChain_Market_Sizing.pdf - page 8 - ©

blog.chainalysis.com/reports/money-supply

medium.com/unchained-capital-blog/bitcoin-data-science-pt-2-the-geology-of-lost-coins-79e5a0dc6d1

wir2022.wid.world/chapter-4

fortune.com/2021/12/20/001-percent-bitcoin-holders-control-nearly-one-third-supply/

bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

danheld.com/blog/2019/1/6/bitcoins-distribution-was-fair

en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Genesis_block

blockchain.com/btc/address/1A1zP1eP5QGefi2DMPTfTL5SLmv7DivfNa?page=654

bitcoin.stackexchange.com/questions/10009/why-can-t-the-genesis-block-coinbase-be-spent

en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Genesis_block

danheld.com/blog/2019/1/6/bitcoins-distribution-was-fair

bitpanda.com/academy/en/lessons/what-does-pre-mined-mean

icomarks.com/icos?status=presale_active

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_bitcoin#2011

danheld.com/blog/2019/1/6/bitcoins-distribution-was-fair

gfinityesports.com/cryptocurrency/-when-did-dogecoin-start-trading-what-price-did-dogecoin-start-at-when-did-dogecoin-become-popular

icodrops.com/ethereum

washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2014/01/03/hal-finney-received-the-first-bitcoin-transaction-heres-how-he-describes-it

river.com/learn/is-bitcoin-fair

decrypt.co/36210/researcher-finds-more-of-satoshi-nakamotos-lost-bitcoin-fortune

river.com/learn/is-bitcoin-fair

lynalden.com/bitcoin-ponzi-scheme

jstor.org/stable/1909675

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2021.730122/full

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2021.730122/full

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbloc.2021.730122/full

blog.parsiq.net/distribution-of-wealth-in-cryptocurrencies

researchgate.net/publication/357196737_Characterizing_Wealth_Inequality_in_Cryptocurrencies

cylynx.io/blog/on-chain-insights-on-the-cryptocurrency-markets

cylynx.io/blog/on-chain-insights-on-the-cryptocurrency-markets

blog.dshr.org/2018/10/gini-coefficients-of-cryptocurrencies.html

blog.dshr.org/2018/10/gini-coefficients-of-cryptocurrencies.html

bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=51011.msg608239#msg608239

vitalik.ca/general/2021/07/29/gini.htmlrrrr

vitalik.ca/general/2021/07/29/gini.html

researchgate.net/publication/357196737_Characterizing_Wealth_Inequality_in_Cryptocurrencies

researchgate.net/publication/357196737_Characterizing_Wealth_Inequality_in_Cryptocurrencies

blog.parsiq.net/distribution-of-wealth-in-cryptocurrencies

buybitcoinworldwide.com/how-many-bitcoin-users

blog.chainalysis.com/reports/2021-global-crypto-adoption-index

bitcoinist.com/how-bitcoin-adoption-rate-is-beating-the-internet

hbr.org/2013/11/the-pace-of-technology-adoption-is-speeding-up

chaindebrief.com/cryptocurrency-adoption-curve-is-the-fastest-in-human-history

danheld.com/blog/2019/1/6/bitcoins-distribution-was-fair

bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=375643.0

unchained.com/hodlwaves

unchained.com/hodlwaves

insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin-supply-distribution

insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin_holders

marketgit.com/why-are-some-countries-good-at-adopting-new-technology-while-others-are-not/

unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tir2020_en.pdf

ft.com/content/1ea829ed-5dde-4f6e-be11-99392bdc0788

tradingeconomics.com/country-list/inflation-rate

fidelitydigitalassets.com/bin-public/060_www_fidelity_com/documents/FDAS/2021-digital-asset-study.pdf

populationpyramid.net/northern-america/2020 and populationpyramid.net/europe/2020

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/11/16-of-americans-say-they-have-ever-invested-in-traded-or-used-cryptocurrency/

globalfindex.worldbank.org/sites/globalfindex/files/chapters/2017%20Findex%20full%20report_chapter2.pdf

youtu.be/K4ybaPFk8IM?t=241 (Frankfurt School Blockchain Center)

pewresearch.org/global/2015/04/15/cell-phones-in-africa-communication-lifeline

ourworldindata.org/internet

researchgate.net/publication/340536565_The_impact_of_monetary_systems_on_income_inequity_and_wealth_distribution_A_case_study_of_cryptocurrencies_fiat_money_and_gold_standard

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Cantillon

researchgate.net/publication/340536565_The_impact_of_monetary_systems_on_income_inequity_and_wealth_distribution_A_case_study_of_cryptocurrencies_fiat_money_and_gold_standard

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3319688

visualcapitalist.com/distribution-of-global-wealth-chart

visualcapitalist.com/distribution-of-global-wealth-chart

oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621341/bp-inequality-kills-170122-summ-en.pdf

credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/global-wealth-report.html

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3319688

wir2018.wid.world/executive-summary.html